|

| Taryn Simon in front of one of her works |

I was inspired by the layout of Taryn Simon's latest exhibition, A Living Man Declared Dead, and also by its presentation of a snapshot of humanity:

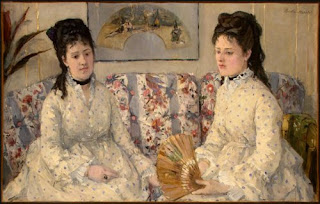

An artist who wants to photograph absence and organise chaos, Taryn Simon is nothing if not ambitious. Previous pieces have seen her gaining access to the secret facilities of America, photographing victims of miscarriages of justice and spending four days without sleep documenting confiscated items at JFK airport, but it is her latest work, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters, which is her most complex project yet. Spanning four years and as many continents, it is a visual and textual record of the bloodlines of eighteen individuals, and the narratives that accompany them. The scope is vast, both geographically-in one room you can go from Nazi occupied Poland to Hussein’s Iraq and then on to Communist China- and socially-touching on issues including the criminalisation of homosexuality, thalidomide pregnancies and the genocide of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims- you get the sense that Simon, like an epic poet, is not attempting to photograph people, but fate. This is a work which shows vividly how the outside world- religion, war, governance-impacts on the individual, and questions what this means for the human race as a whole.

To answer some of life’s biggest questions in just eighteen photographic studies is no mean feat, but Simon takes it in her stride. She admits that she is drawn to ‘projects that end up being incredibly laborious’, which is something of an understatement in terms of this particular project. Of those four years she spent working on it, just two months were spent shooting, the rest on preparing to shoot- researching the bloodlines, working out the logistics, organising the translators, etc. This meticulous, almost obsessive approach translates to the presentation of the chapters, as Simon calls them, that make up the overall work- there is one, precise format which all must conform to. You could spend more time examining the notice at the start of the exhibition explaining the ordering of the photographs alone than the works themselves, though it is important that you do, because an appreciation of Simon’s work rests on an understanding of her method.

|

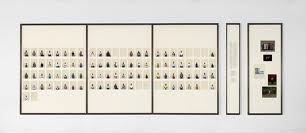

| Example layout |

Each chapter has three panels, the first being the photograph panel, in which images of each member of the bloodline are systematically ordered. All Simon’s subjects are photographed against a neutral cream background, which she calls ‘the non-place’, to strip away any context and sense of environment. The result is a periodic table of people, and this scientific approach is epitomised in Simon’s cataloguing even those relatives who are dead, missing or refused to be photographed- they are represented by an empty shot of the same background. Viewing these images and then reading the information in the next panel, the text panel, produces a startling effect- a kindly looking old man is revealed to be a polygamist whose wives have been given to him in payment for the spiritual treatments he offers, one unassuming looking family transpire to be the relatives of Hans Frank, Hitler’s legal advisor and the governor of occupied Poland, a major perpetrator of the Holocaust. It is hard not to reconsider the photographs in this new light, that which, with its strains of violence and corruption, frustrates any attempt at control and order, no matter how precise.

Simon calls the third and final panel the footnotes panel, but the images it presents are anything but secondary to the story; they are not just the evidence of this narrative but parts of others. In the first chapter, that which gives the work its name, the evidence is the record which show how Shivdutt Yadav’s relatives declared him dead so they could take his land, and a letter to a judge which states that he is, in fact, alive, and would like to take legal action against his relatives. But perhaps the most interesting image is that which shows a headless and bloated corpse floating in the Ganges River. It links to the main story in that the father of the so-called ‘dead man’ was cremated and his ashes scattered in the river, but also alludes to the issue of leprosy in India, because the body is that of a sufferer. In this way, the stories begin to seep out of the frames that they are confined to, and so Simon, unbelievably, extends her concerns even wider. And, just like previous panels, this panel informs and is informed on those that precede it- its abstract presentation jars with that of the portraits, as Simon acknowledges that life cannot be ordered and contained, and, when viewed in conjunction with the text, simple objects presented in it become symbols, weighted with new meaning- a videogame is explained to have been created by a South Korean game designer who was abducted by the North Korean government, a framed inscription reading ‘Those who do not know their past are not worthy of their future’ in a classroom is revealed as hanging cruelly over the heads of orphans in Ukraine, who have no genealogy to trace, and in whose future lies, in all probability, trafficking, prostitution and involvement in crime. In placing these three panels together, combining portraiture with reportage and realism with conceptualism, Simon confounds attempts to define her work- posing the question of whether it is photography, documentary or fine art that has so frustrated critics- and does full justice to the narratives she has uncovered.

However, having delineated Simon’s format and its importance, it is often the variation of that system which is most evocative. The titular chapter is no doubt interesting, and indeed Simon’s decision to name the work as such comes from its strange irony- she is photographing a man who legally does not exist, though her photograph proves exactly the opposite- and the fact that she believes it establishes a metaphor which can describe the whole piece, that of photographing absence, but it is many of the ‘Other Chapters’ of the title that, though less-publicised, are most captivating.

In one chapter, there are several rows of individuals pictured before we reach one ordinary looking man, and his cycle then continuously repeats to fill the rest of the frame. This young man in fact belongs to the Druze, a religious community whose eclectic set of beliefs includes one in reincarnation. His family believe that he is a reincarnation of his grandfather, hence the repeating pattern, as he is both his father’s son and his father’s father. Simon says that the piece ‘tries to consider the idea that we keep going, people keep being produced. And does that all amount to some sort of evolution, or are we on repeat?’ Thus this story, linking as it does to several of the other chapters in querying the course and purpose of human existence, would describe the questions Simon seems to be asking throughout the work far better than its actual title.

In another chapter, two photograph panels are presented side by side. At first glance the individuals could be taken as belonging to the same family, but the text reveals that they are in fact two separate families, the rivals in a Brazilian blood feud spanning several generations. Simon seems to anticipate the viewer’s original, mistaken action, questioning why we fight one another if we are so similar, and not just on the small scale of these physically similar individuals, but on a global scale, the similarity being that we are all of the same species. Another temptation with this chapter is, having read the text, to compare the opposing pairs of individuals by age, viewing them as Montagues and Capulets and searching for a Romeo and Juliet. This tendency to romanticise also seems expected by Simon, and, as she shows in the footnote panel with the lists of the dead, there is no such Hollywood glamour to this real life tragedy.

Sometimes these changes in form need no explanation, but have just as great an effect- in many chapters, the blank spaces are filled by other representations of the missing individual, such as clothes they have sent to Simons. This asks questions itself, about how we choose to present ourselves, which is another entire study which could be undertaken of the whole work, as every person photographed has chosen the clothes they are wearing for a reason, but more chilling are the photographs of bones, teeth and other mortal remains used to represent deceased family members. Though they are interspersed with photographs of living descendants, the youngest of which is a smiling baby, the message is unclear- perhaps it is of hope in a seemingly bleak situation, perhaps it is of despair in an outwardly happy one, given that the image of the baby is followed by one of a decaying bone, possibly envisioning the unhappy future.

In still more chapters, it is possible to see the tragedy entirely from the images alone, and this actually makes for some of the most emotionally powerful viewing experiences in the exhibit. The one thing that all these bloodlines have in common is that each member bears a physical resemblance to the other members of that family, except for that of the albino individuals. Their dissimilarities to their family are obvious, and this points out how difficult it is to be different, and to be clearly seen as such. The other unique chapter in this respect is that which features pictures entirely of children. Not only are they are completely different, but, unlike all the other pieces, even that which focuses on rabbits, they do not have a point person- Simon’s description of the one individual in a bloodline who the narrative is centred around-nor even a coherent bloodline, thus their visual disparity points out how alone they are. There has been a great deal of criticism about Simon’s combination of text and photography, with some arguing that a great photograph should speak for itself, whilst the impact of her images depends on her writing. In fact, as these chapters show, the photographs can be just as significant alone.

But perhaps the most telling variation on the format is that chapter which takes as its subject the only non-humans in the exhibition- several families of rabbits, the subjects in a government controlled experiment in Australia to test methods of controlling their population. There are no blanks here, as the rabbits have no choice, which can however, rather uncomfortably, be compared to the family whom the Chinese government have chosen to be the face of China, and thus be seen as an extension of Simon’s ideas about the way humans treat one another. Another uncomfortable question to consider here, prompted no doubt by Simon’s decision to place this chapter not at the end, but right in the middle of the human bloodlines, is whether we humans too are not just multiplying out of control, and indeed after a while viewing the exhibitions, the people become just as identical as the rabbits are to one another. However, on closer inspection, each rabbit has its own individual pose, perhaps reversing Simon’s statement entirely, instead forming a comment on how we have forgotten how to treat one another as individuals.

Indeed, just within the confines of this exhibition, it is easy to feel lost among all these faces, to lose your identity as an individual as theirs is defined, especially if you feel that you do not have as interesting a narrative. This is, one senses, exactly what Simon intended to do- confront us with the enormity of existence. Her choice to exhibit such a variety of stories altogether is a deliberate one- these 18 chapters seem massive, and yet this is far, far less than even 0.1% of the world population. It is difficult to look at just one chapter and consider that each person pictured is an individual, and has their own thoughts and feelings, let alone eighteen chapters-let alone the nigh infinite numbers of chapters that truly exist.

And it is in this maelstrom that Simon seeks to find meaning. She has stated before, contrary to the beliefs of prominent critics (Salman Rushdie has called her ‘an invaluable counter-force in a world in which the truth is concealed’), that she has no political agenda, but that she is interested in the abuse of power, and the role of photography. But were this piece merely motivated by that, this piece would not carry half so much of its power. Yes, a certain amount is conferred on it by the passion Simon evidently feels for the causes, which often undermines the scientific detachment of her lists of names, jobs, and reasons for non-participation, but the rest comes from how personal the project seems. Simons has stated that ‘The works are attempting to map the relationships among chance, blood and other components of fate; trying to see or struggling to find some sort of code or pattern embedded within that’, and it would seem that part of her interest is in placing herself within that pattern, particularly as she has also described life as kind of this unending machine- like a churning out of stories and individuals, and to what end is completely unknown. I guess I’m trying to organise it for myself.’ After all, one does not obsessively research eighteen bloodlines without having some questions about their own identity, and indeed Simon has stated that her work is ‘underpinned by anxiety’. The work gives the sense that the identity in question is not hers as a family member, but as a member of the human race. Questions about our morals and the reason for our existence our rife in Simon’s works, only dominated perhaps by the questions about time. Photography captures a moment in time, and Simon seems to be trying to extend this by bringing the past and present together and freezing them- seeing if any narrative can be without motion. However, the fact that there is so much movement, particularly in the suggestions about the future, illustrates precisely her metaphysical anxieties, ‘the work does seek to look at stories and individuals as past’s future and future’s past, and these ideas of repetition and even that we are all sort of ghosts of another time and a time to come’. Many of the chapters explore ideas of this kind, reincarnation in particular, is a theme, suggesting that Simons is perhaps looking for something more than what she largely discovers- death and absence.

Whether Simons has managed to answer any of her questions is unsure, certainly she has said that she doesn’t ‘know if there is an answer’ to the meaning of life, and the fact that her works pose more questions than they answer her original one seems to support this. If she has managed to place herself is dubious too, given how easy it is to feel lost among all these faces as an individual, let alone as the artist, and one cannot help but notice that amongst all these families, her own is not featured, and wonder why (especially given that there is no lack of an interesting narrative there- she is, after all, married to Jake Paltrow, brother of Gwyneth.)

Despite these unanswered questions, at least one has been solved. Simon has always been concerned about the role of photography and its limits, and here she has exposed them entirely, acting as detached documenter and removing all extraneous details, using her camera, as she puts it, as ‘a simple recorder’. Of course, this in its turn asks another question, what is next for a young woman who has already received the rare accolade of a major exhibition at the Tate, for a photographer who says that she has ‘just gotten tired of photographs’? One thing’s for sure, if it’s anything as thought provoking and captivating as this work, she will be receiving even rarer accolades in the future.